You see gears in just about everything that has spinning parts. For example, car engines and transmissions contain lots of gears. If you ever open up a VCR and look inside, you will see it is full of gears. Wind-up, grandfather and pendulum clocks contain plenty of gears, especially if they have bells or chimes. You probably have a power meter on the side of your house, and if it has a see-through cover, you can see that it contains 10 or 15 gears.

Gears are everywhere where there are engines and motors producing rotational motion. Read on to learn about gears, gear ratios and gear trains so that you can understand what all the different gears you see are doing. Safeguard Gearbox

Gears are generally used for one of four different reasons:

Understanding the concept of the gear ratio is easy if you understand the concept of the circumference of a circle. Keep in mind that the circumference of a circle is equal to the diameter of the circle multiplied by pi (pi is equal to 3.14159...). Therefore, if you have a circle or a gear with a diameter of 1 inch, the circumference of that circle will be 3.14159 inches.

Let's say that you had two circles: one with a diameter of 1.27 inches and another with a diameter of 1.27 inches / 2 = 0.635 inches. The larger of the two circles has a circumference of 4 inches.

If you rolled both circles, you would find that the smaller one has to complete two full rotations to cover the same 4-inch line as the larger one. This explains why two gears — one half as big as the other — have a gear ratio of 2:1. The smaller gear has to spin twice to cover the same distance covered when the larger gear spins once.

Most gears that you see in real life have teeth. The teeth have three advantages:

To create large gear ratios, gears are often connected together in gear trains, as shown here:

The right-hand (fuchsia) gear in the train is actually made in two parts, as shown. A small gear and a larger gear are connected together, one on top of the other. Gear trains often consist of multiple gears in the train, as shown in the following two figures:

In the case above, the fuchsia gear turns at a rate twice that of the purple gear. The green gear turns at twice the rate as the fuchsia gear. The pink gear turns at twice the rate as the green. The gear train shown below has a higher gear ratio:

In this train, the smaller gears are one-fifth the size of the larger gears. That means that if you connect the purple gear to a motor spinning at 100 rpm (revolutions per minute), the green gear will turn at a rate of 500 rpm and the pink gear will turn at a rate of 2,500 rpm.

In the same way, you could attach a 2,500 rpm motor to the pink gear to get 100 rpm on the purple gear.

If you can see inside your power meter and it is of the older style with five mechanical dials, you will see that the five dials are connected to one another through a gear train like this, with the gears having a ratio of 10:1.

Because the dials are directly connected to one another, they spin in opposite directions (you will see that the numbers are reversed on dials next to one another). For more information on gear ratios, visit our gear ratio chart.

There are many other ways to use gears. For example, you can use conical gears to bend the axis of rotation in a gear train by 90 degrees.

The most common place to find conical gears like this is in the differential of a rear-wheel-drive car. A differential bends the rotation of the engine 90 degrees to drive the rear wheels:

Another specialized gear train is called a planetary gear train. Planetary gears solve the following problem. Let's say you want a gear ratio of 6:1. One way to create that ratio is with the following three-gear train:

In this train, the red gear has three times the diameter of the yellow gear, and the blue gear has two times the diameter of the red gear (giving a 6:1 ratio).

However, imagine that you want the axis of the output gear to be the same as that of the input gear. A common place to need this same-axis capability is in an electric screwdriver. In that case, you can use a planetary gear system, as shown here:

In this gear system, the yellow gear engages all three red gears simultaneously. They are all three attached to a plate, and they engage the inside of the blue gear instead of the outside.

Because there are three red gears instead of one, this gear train is extremely rugged. The ouput shaft is taken from the plate, and the blue gear is held stationary. You can see a picture of an two-stage planetary gear system on the electric screwdriver page.

Finally, imagine the following situation: you have two red gears that you want to keep synchronized, but they are some distance apart. You can place a big gear between them if you want them to have the same directions of rotation:

Or you can use two equal-sized gears if you want them to have opposite rotational direction:

However, in both of these cases the extra gears are likely to be heavy and you need to create axles for them. In these cases the common solution is to use either a chain or a toothed belt, as shown here:

The advantages of chains and belts are light weight, the ability to separate the two gears by some distance, and the ability to connect many gears together on the same chain or belt.

For example, in a car engine, the same toothed belt might engage the crankshaft, two camshafts and the alternator. If you had to use gears in place of the belt, it would be a lot harder!

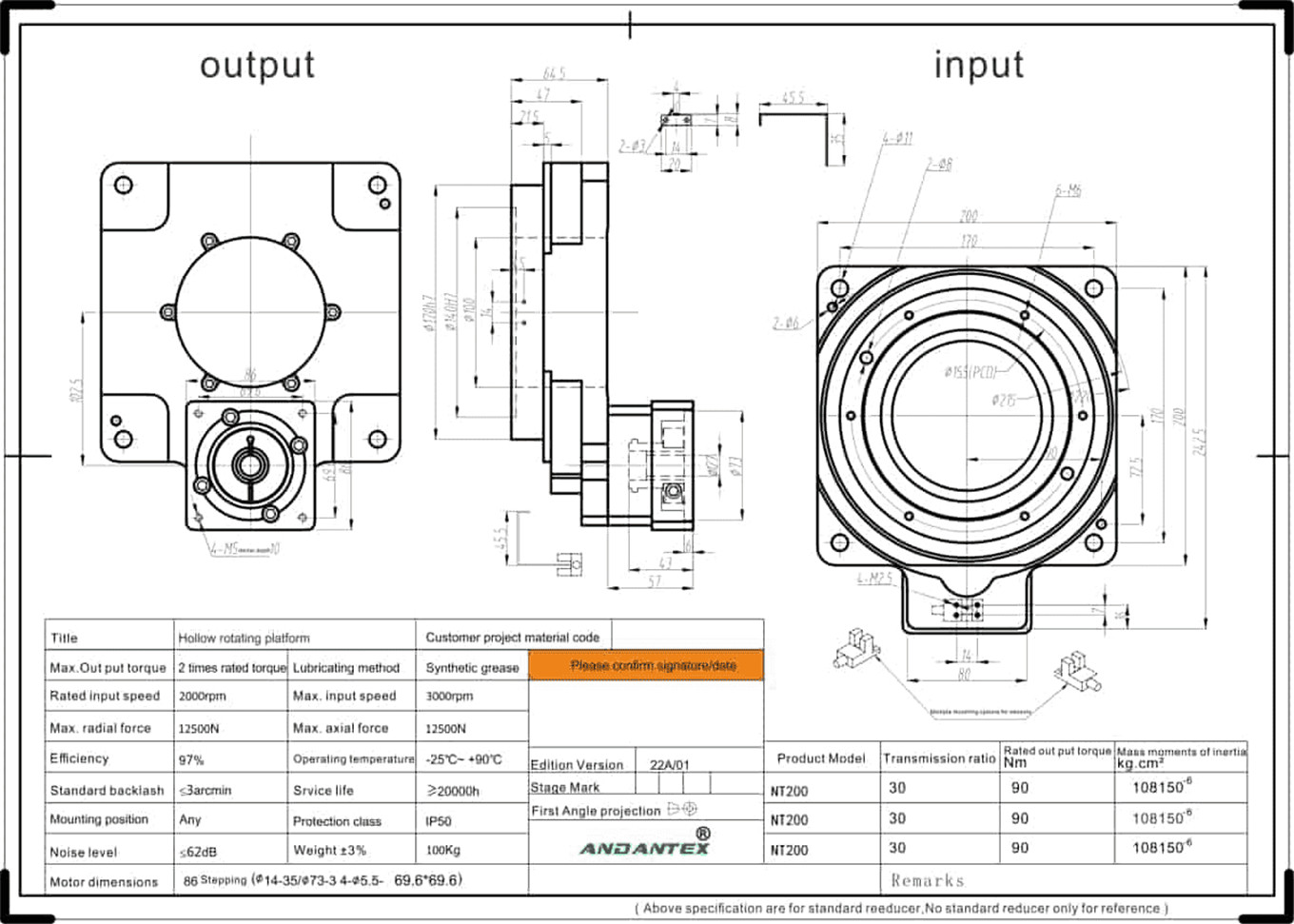

Planetary Gearbox Design Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article: